How did the desire to make this movie come about?

I was first inspired to make this movie back in the fall of 2008 while editing a book called Her Gates Will Never Be Shut: Hope, Hell and the New Jerusalem by Brad Jersak. Brad’s approach to the subject was simple: If we’re going to be biblical about hell, let’s really be biblical. In other words, rather than reading the text selectively to support what we already believe, let’s set our theological biases aside and listen to everything the Bible has to say about post-mortem punishment. That means examining all of the words typically translated as hell (sheol, Gehenna, Tartarus, Hades), all of the images of judgment (the lake of fire, outer darkness, etc.) and various interpretive traditions throughout Jewish and Christian history.

I came away from that experience realizing the Bible is absolutely polyphonic on this issue. Contrary to popular belief, there is no single, unified voice speaking throughout the text. Instead, some voices cry out for divine wrath and punishment. Others beg for mercy. Some seem to indicate that the wicked will suffer for eternity. Others imply the wicked will be utterly destroyed. And still other voices hold out hope that all people will ultimately be reconciled to God. What are we to make of this? I think many Christians—particularly evangelicals—go to the Bible expecting to find a series of objective statements that will settle the matter decisively. Instead we find a lively conversation where competing viewpoints aren’t just maintained, they’re encouraged. This might be problematic for some Christians who mistakenly regard the Bible as a single book. However, if we understand the Bible for what it truly is—a theological library—this is exactly what we should expect to find. I take this as an invitation to continue the conversation today, making sure not to shut down dissenting voices.

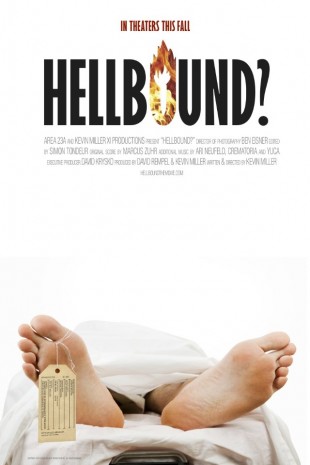

I knew right away I wanted to make a film on this topic, because I suspected most Christians (and non-Christians) were as ignorant as I was before I started on Brad’s book. We’ve all heard the “hell story,” and we all assume there is really only one way of looking at it—at least if you want to call yourself an orthodox Christian. I was eager to explore alternate ways of reading the text to see if you really could maintain an alternate view, such as universalism, and still regard yourself as a thoroughly biblical and Christ-centered believer.

It wasn’t until January 2011 that I finally found myself in a position to think seriously about making the film. I was about to turn 40, and after years of working as a screenwriter-for-hire, I decided it was finally time to strike out on my own. Call it a mid-life crisis. So I literally started doing one thing each day to make the film a reality. That led to two things per day and more until I found myself working on it full time—booking interviews, budgeting, etc.—all without a single dollar behind the project.

About two months into this process, Rob Bell came out with his book Love Wins. Within weeks, hell was literally on the front page of TIME magazine. So if I had any doubts about the timeliness of the topic, they were quickly erased. But I still didn’t know how I was going to pull the film off.

Finally, about three weeks before production was slated to begin, I connected with an investor named Dave Krysko who bought into my vision. Before we knew it, we were flying to Copenhagen to do our first shoot.

Why has death become a subject you wanted to discuss?

I’m not sure how much other people think about death, but I tend to dwell on it a lot, especially now that I have children. I’m always doing mental calculations to figure out how long I’ll get to spend with them if I reach my target age of 98 years. (I don’t know why I chose that figure, it just feels right. I may change my mind when I’m 97 though…)

More seriously, I’ve never really thought of Hellbound? as a discussion about death. Instead, it’s really a discussion about the nature of God, the Bible, justice, freedom, evil, how we form beliefs and those sorts of issues. However, the further I’ve traveled down this road, the more I recognize the power of death as a driver of human behavior—particularly our anxiety about death.

One of the key influences on me during the making of this film is Ernest Becker, who is perhaps best known for his book The Denial of Death. In it, he argues that virtually all of human behavior is driven by our fear of death. Faced with the terrifying certainty of our imminent demise, we devise immortality systems that will allow us to transcend death, either figuratively—by creating a work of art or a large building that will live on after we die—or literally through belief in something like the resurrection of the dead. Even having children can be seen as a reaction to death anxiety, because it assures us that part of us will live on after we die.

Death anxiety has led to all sorts of great human achievements, but they come at a price. And more often than not, death anxiety tends to make us self-centered, defensive, acquisitive and, ultimately, violent. Because if someone threatens our immortality system, we only have a few options—win them over to our side or find a way to silence their dissent, possibly for good.

Once you begin to recognize the wisdom of Becker’s observations, it changes the way you look at Christianity, particularly the Resurrection. At a certain point during the production I found myself wondering about the central predicament of humankind. The way many Christians understand it, our central problem is that we have angered a holy God with our sin. Someone has to pay the penalty for our crimes. We are unable to do it, so Christ offered to do it in our place. Now we can have peace through God, because he has essentially satisfied his wrath by taking it out on his son. We can either accept Christ’s suffering in our place or else bear the punishment for our sins forever in eternity.

The more I pondered that story, the less sense it made, because if you think about it, it’s all about the Crucifixion—paying the penalty. The Resurrection is merely a bonus—a reward for making the right choice.

However, as I reexamined Christianity through the lens of Ernest Becker, I came to see that if the central problem of humankind is fear of death, then the Crucifixion is all about facing that fear, and the Resurrection is about overcoming it. If fear of death truly is the driving force behind our self-destructive behavior—that is, if we are “gods with the bodies of worms,” as Becker described us, where the specter of death haunts us even on the most sun-filled of days—then defeating death would be the ultimate solution to all of our problems. (This is certainly what Hebrews 2:14-15 seems to indicate: “Since the children have flesh and blood, he too shared in their humanity so that by his death he might break the power of him who holds the power of death—that is, the devil —and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death.”) This moves the Resurrection front and center in the Christian faith, which is exactly where it should be. It’s also consistent with the way the gospel is preached in the book of Acts and in Paul’s letters. You never see the Good News phrased this way: “Good news! You don’t have to go to hell when you die!” Instead, what you hear over and over again is, “Good news! Death is not the end!” See the way Paul summarizes the gospel in 1 Corinthians 15, for example. The crucifixion is mentioned of course, but it’s the Resurrection that’s central. The same goes for Romans 5, where Paul explicitly explains that Christ has reversed the pattern of death set by Adam.

I could go on (I have gone on!), but the point is, this perspective caused me to seriously rethink the substance of the good news we are sharing. Is this all about satisfying an angry God, or it God’s way of setting us free from our own anger and violence, which we so naturally project onto God?

What led you to include footage/perspective from the Fred Phelps camp?

Like it or not, hell has become a sort of litmus test to help determine whether you’re “one of us” or “one of them.” Many people have a tremendous sense of certainty that they, and only they, have the correct belief on this topic. When you challenge their belief, they get angry, and they may even expel you from their fellowship—as has happened to several pastors over the last few years. I think this is a good picture of death anxiety at work. When you question someone’s belief in hell, you cut to the heart of his or her immortality system. So you must either be silenced or expelled.

Alongside hell, this demand for theological unanimity is something I really wanted to tackle in the film. If you break the film down into three acts, I would call Act 1 “Certainty,” Act 2 “Ambiguity” and Act 3 “Humility.” So as I cast about looking for a group who represented absolute certainty about their beliefs and a willingness to damn others to hell—literally—for disagreeing with them, I could think of no better group than the Westboro Baptists. On one level, I hate to give these people more press. But at the same time, we draw connections between what the Westboro Baptists believe and what other more socially acceptable groups believe in order to reveal that even though the packaging may be different, the message is essentially the same. You may not like the Westboro Baptists, but at least they don’t try to hide the ultimate implications of their beliefs—which is more than I can say for some of these other groups.

How awkward or difficult was it for you to remain objective and balanced in airing various viewpoints of Hell, God, Christianity, Jesus, etc?

The question of objectivity always comes up around documentaries. I think this represents a bit of naivety on the part of viewers. My facetious answer is that Hellbound? is about as objective as the people watching it, which is to say, not very! What people don’t realize is that the moment you decide to interview one person and not another, to film one event and not another, to point your camera in one direction and not another, to choose one shot and over another in the editing room and so on, it’s subjectivity all the way down. I think people try to hold filmmakers to a level of objectivity they are unwilling to abide by themselves. None of us are objective beings; we all experience the world subjectively, so naturally any work of art is going to reflect the filmmaker’s bias. The only relevant question to my mind is, are you aware of your bias? If so, are you able to defend it?

That said, I think it’s important to distinguish between objectivity and balance. A film can lean in a particular direction, but not at the exclusion of counter-arguments. I like to think that the difference between propaganda and art is that propaganda gets its power from showing only one side of an issue—by suppressing or distorting counter-arguments. Art gains power by showing all sides of an issue. I’m hoping people agree that Hellbound? leans more toward the art side of the spectrum.

What parts, themes, interviews, segments during the making of this movie were the most challenging? Why?

Filming at Ground Zero during the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks was by far the most challenging shoot from a logistical point of view. Never mind the security required for the memorial ceremonies, the city was also in lock-down mode due to a threatened terrorist attack. When we rolled into Lower Manhattan at about 5am that morning, it felt like we had arrived in Gotham City right when they were preparing for an all-out assault by the Joker. Armored vehicles, machine guns, guard towers, canine teams and hundreds of police officers were everywhere. It was almost impossible to get to where we needed to film. It took a while, but we were finally able to find our way through.

Personally, one of the most difficult interviews was my interaction with the Westboro Baptists. Margie Phelps in particular was highly antagonistic and difficult to manage. We also attracted quite a crowd, so it was a real challenge for me to stay on point and to keep my cool. I didn’t always succeed, but I think the interview went pretty well overall.

What have been some of the reactions from people watching the movie?

We haven’t shown the film to too many people yet, but so far the reaction has been overwhelmingly positive. That’s been really encouraging. I know that can’t last for too much longer. There’s no question this film is going to rattle some cages. But I’ve been through that sort of thing before on other films, so I’m reasonably prepared for it… I think.

What Christian metal / hard music (if any) have you associated with the film (soundtrack,etc)?

We have two metal songs in the film, but neither is by a Christian band. They’re actually by a band called “Crematoria” that we met while filming at a death metal festival in Copenhagen. We do have a couple of other songs in the film by artists who would define themselves as Christians, but neither falls into the metal/hard music category. That said, as we’ve been promoting the film at various Christian music festivals across the USA, we have met several Christian metal bands, many of them quite good. Had I known about some of them sooner I may have pursued them to participate in the film.

What/how/why did heavy metal come up in the movie?

I’ve been a metal fan since I was a kid—literally since I was five years old. So I’ve always associated metal with images of hell, Satan, death, etc. I found it interesting to think that for Christians, hell is a place best avoided. But metal fans embrace it. In fact, they form communities around the idea. Our first shoot actually took place at a death metal festival called “Copenhell” in Denmark. That same weekend we could have been at Hellfest in France. Or we could have filmed at stop on Slayer and Rob Zombie’s “Hell on Earth” tour. We could also have chosen to shoot at the Damnation Festival in England. The question is, why? What’s the fascination? Do these bands—and their fans—really believe in hell or is something else going on? So we interviewed a number of metal bands and fans to get their perspective. I have to admit I was a bit intimidated going in. From a distance, some of these people look pretty scary. But I was surprised to discover they were surprisingly thoughtful—and friendly! Showbiz certainly plays a role in what they do, but try as we might, we couldn’t find anyone who actually believed in any sort of dark power. I think a better way to describe much of the metal scene is “atheism with distortion.”

If you could stand up on stage after each screening and tell the audience one or two things, what would you say or ask?

That’s a tough one. I have a hard time staying in the theater when someone is watching my film, much less deliver a speech afterwards. Ultimately, I would say Hellbound? is an argument for curiosity, humility and acceptance of those we are prone to instinctively reject as “the other.” So to Christians, what I would say is, even if you don’t agree with the film’s point of view, take a second look at what you believe, why you believe it and the effect it’s having on the world. Too often allow our beliefs about the future (which we can’t prove) to turn us into jerks today. So my advice is to deal with the jerk today. I don’t care how right you think you are. If you’re using your beliefs to bludgeon other people, to ostracize them, etc., that pretty much tells the story. Your life is the best interpretation of your beliefs.

To non-Christians, I would encourage them to take a second look at Christianity. I’m hoping that by the end of the film, they will realize that perhaps they rejected Christianity without ever having actually experienced it. I truly believe the Gospel represents “deep wisdom from the dawn of time” or, as Rene Girard puts it, “things hidden since the foundation of the world.” So I’d hate to see anyone miss out on it. Never mind our eternal fate, I truly believe that the survival of the species—of all species—is contingent on our ability to grasp the freedom from our death-driven culture that Christ has to offer.

Copyright © 2012 HM Magazine, LLC. All rights reserved.